In the middle of the 18th century, a minority of painters – including Oudry and Natoire – still stubbornly grinded malachite to obtain green rather than mixing blue and yellow. At the dawn of the 19th century, however, whole new perspectives await this stone. In 1758, the Russian metallurgical magnate Alexei Turchaninov acquired the Gumyoshevsky mine, where he began extracting the green mineral, which has long been exploited for its wealth of copper. Quickly, the entrepreneur manages to value this stone to the point of exploding its demand. From the 1770s to the 1810s, Turchaninov was the main supplier of malachite to Russia and Europe for the creation of small decorative objects. For the moment, the lapidaries have come up against the softness of this stone, resigning themselves to using it in small veneers associated with other materials. Malachite frames or serves as a background, it underlines and enhances, like the bronze with which we begin to associate it; the result is indeed very nice.

Nicolas Demidov (1773 – 1828), whose family owns lapidary workshops and operates the mines of Nijni Taguil or Yekaterinburg, in 1819 ordered the bronzier Thomire (1751 – 1843) to mount a monumental vase in malachite, today kept at the MET Museum. A few large objects have already been produced, but it is then a remarkable feat. In 1808, some of these expensive and rare creations were offered to Napoleon I and still decorate the Salon des Malachites at the Grand Trianon today.

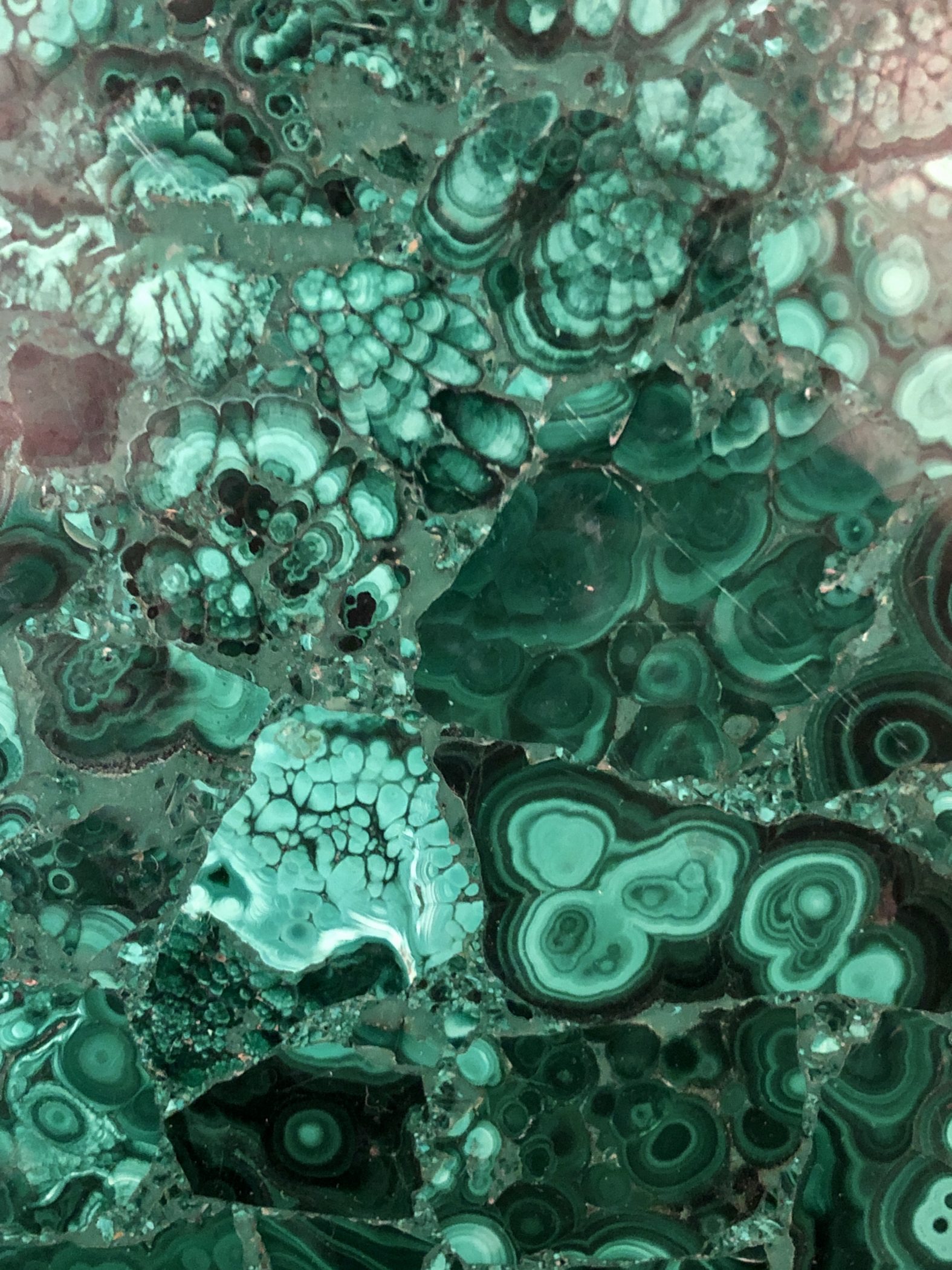

It took many attempts to work with malachite as we usually do with other hard stones. The Florentine lapidary technique was used in particular through the Roman mosaicist Francesco Belloni in Paris and his colleague Luigi Moglia called to Saint-Petersburg by Tsar Nicolas I (1796 – 1855). Soon the Russian manner distinguished itself from the Florentine. While the pietre dure set out to create an artistic motif, the Russian way intended to reproduce the monolithic surface of the stone. It even took the exercise to tackle flat surfaces as well as rounded or raised surfaces.

Russian Lapidary Marquetry

Appeared in the 1780s, the Russian style therefore gives up shaping malachite in its mass and employs, for both small and large decorative art objects, a core of metal or, more rarely, limestone from Putilov. Thin strips of malachite 2 to 4 millimeters thick are glued to the object and the gaps filled with malachite powder mixed with mastic. Everything is polished so as to remove unsightly junctions. Like marquetry, the possibilities of arranging natural stone designs allow for a small range of patterns among which the “crumpled velvet” assembly gives the illusion of a moiré fabric.

The ringed or striated assembly employs parallel bands while the radial produces beautiful ocelli. By selecting slats with repeating patterns and ordering them symmetrically around one or more crossed planes, we obtain a so-called “two-sided” or “4-sided” pattern similar to a pattern reflected in a mirror.

Little by little, the monumental achievements and the rooms of the malachites in the 19th century became synonymous with undeniable prestige. In 1835, the new Saint Isaac’s Cathedral in Saint Petersburg was decorated with nearly 16 tonnes of malachite. In 1826, the Duke of Wellington returned from the funeral of Tsar Alexander I with his arms full with a collection of objects straight from the royal workshops of Ekaterinburg, Peterhof or Kolyvan. Then in 1837, the Winter Palace received its sumptuous malachite room. In Mexico City, at Chapultepec Castle, an identical room is preceded by two monumental doors also in malachite. In Paris in the 1860s, the Hôtel de la Païva received a chimney of this mineral when they were already numerous in Russia at the same time; This is evidenced by that of the Youssoupov Palace in Saint Petersburg.

In the 1860s the decline of malachite began, dethroned by lapis lazuli. Monumental productions that were too expensive were abandoned by the royal workshops, which, along with other private workshops, continued to create small objects, candlesticks, snuffboxes, boxes. Today it is very difficult to distinguish the productions of these different workshops which establish the work of malachite as a Russian art craft. In Russia, the green stone made a deep impression. The collection of stories The Malachite Box, written by Pavel Bazhov between 1936 and 1945 became such a classic that a deluxe edition adorned with malachite was exhibited at the World’s Fair in New York in 1939. At the turn of the 20th century and until the 1930s, malachite lost a time its splendor before Art Deco gave it a new lease on life, give it a sober, elegant and refined modernity. Pietro Fornasetti (1913 – 1988) continued this approach by creating contemporary pieces borrowing as much from the gilding of old bronze mounts as from the decorative arts of the 18th and 19th century. Today, malachite no longer covets the monumental, but its moiré greens continue to delicately transform adornments and small objects into refined jewels.

Marielle Brie

Art Historian for Art Market and Cultural Media

Author of the blog Objets d’Art et d’Histoire

Autres ressources et documentations

27 April 2024

Vienna Bronzes

Collectible objects since their creation, Vienna bronzes play the role of accumulation in bourgeois interiors. They are charming manifestations of the social success of their…

29 March 2024

A Micro-mosaic Grand Tour Cross

An emblematic art of the Grand Tour, micro-mosaics rival painting in its most refined productions.

19 March 2024

The Cordoba Leather or Gilded Leather

This famous leather gave its letters of nobility to Spanish production drawing generously on oriental know-how known since Antiquity.

6 February 2024

A Solid Silver Inkwell, 1860 – 1890

This solid silver inkwell is a true sculpture in itself.

4 December 2023

Chinese Opium Den Pillow, 19th Century

A surprising object to our Western eyes, Chinese rigid pillows have long been preferred to their fabric counterparts.

22 November 2023

Georges Clémenceau (1841 – 1929) Bust

A major politician and major cultural figure, Georges Clémenceau encounters both the First World War and the representatives of an art freed from the codes of the Academy.