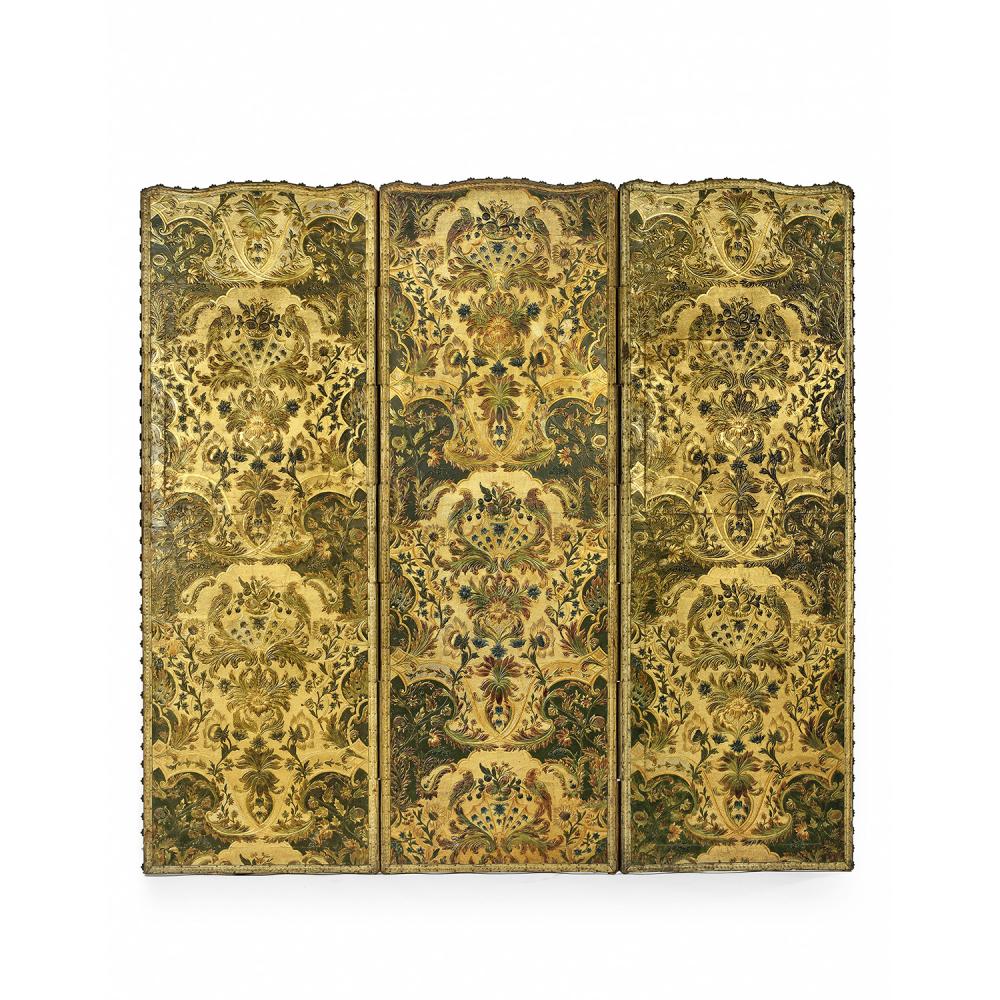

The warm material of leather combined with the play of light of its reliefs thus produces spectacular pieces of decorative arts.

The Cordoba leather, swarthy gold or Spanish skins, all terms covering the same production of Spanish guadameciles, silvered leathers decorated with relief patterns sometimes painted or gilded. Renowned and sought after until the end of the 18th century, this ancient leather craft acquired its letters of nobility in the Libyan town of Ghadamès which, it is said, gave its name to the technique reused and perfected by the Andalusian Hispano-Moorish people. Although virtually no fragments survive before the 15th century, this art dates back to the 9th century.

Be careful to distinguish between two false friends: Cordoba leather (which will give us our word “shoemaking”) is not Cordoba gilded leather. While the first is a goatskin, the second is a basane (sheepskin) which serves as a support for the guadamecil. In the 16th century, Barcelona and Cordoba (which did not have the Spanish monopoly on leather production), only authorized ram leather for this art with which chairs, chests, screens, altar fronts and all other sorts of objects of devotion were covered, when they were not used as wall coverings. The expensive raw material predestined the use of these leathers to luxury, which required long and laborious preparation. After having thinned and stretched the skin for a long time, the craftsman cut it into tiles of regulated size (75 x 65 cm in Cordoba). Then each tile was coated with glue or egg white in order to adhere a silver leaf to it. The operation was repeated on the latter in order to protect the metal from oxidation. Then, the relief decoration was deeply engraved or stamped by hand before being directly painted on the silver leaf, the only effective way to maintain it on the leather without it crumbling. This silver support gave the paintings a special shine that is still visible today, even on the oldest leathers. By applying a yellow varnish to the metal leaf, long known to the Byzantine world, the silver was given the appearance of gold leaf which was never used on leather. From the reliefs of the stamping and the luminosity of the silver were born spectacular productions appreciated and exported, at least from the 14th century, in France and Italy but also in Flanders.

The movement of craftsmen favored the diffusion of techniques and by the 1630s, Flanders surpassed Spanish mastery. French calfskin, fine and resistant, was preferred to sheepskin and imported to Flanders where it was worked mechanically: embossed using wooden molds and counter-molds or embossed using heated and applied metal plates. in press. By varying the quality of decorations and leather, production in northern Europe drastically reduced costs. The decorations sometimes reached 2 or 3 cm in relief, a modeling impossible to obtain by hand and a characteristic signature distinguishing the guadameciles of Flanders from those of Spain. In the 18th century, leather hangings were produced and demanded everywhere, from Portugal to Poland, Germany and England. The patterns followed the fashions, particularly those for silks, playing on the effects of light and shadow, shine and colors. Then fabric hangings came for a time to supplant these heavy and expensive skins before wallpaper supplanted them both in the 19th century. Cordoba leather, still produced in France today, remains a luxury craft and its intimate use.

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Art historian for the art market and cultural media.

Author of the blog Objets d’Art et d’Histoire

Autres ressources et documentations

27 April 2024

Vienna Bronzes

Collectible objects since their creation, Vienna bronzes play the role of accumulation in bourgeois interiors. They are charming manifestations of the social success of their…

29 March 2024

A Micro-mosaic Grand Tour Cross

An emblematic art of the Grand Tour, micro-mosaics rival painting in its most refined productions.

6 February 2024

A Solid Silver Inkwell, 1860 – 1890

This solid silver inkwell is a true sculpture in itself.

4 December 2023

Chinese Opium Den Pillow, 19th Century

A surprising object to our Western eyes, Chinese rigid pillows have long been preferred to their fabric counterparts.

22 November 2023

Georges Clémenceau (1841 – 1929) Bust

A major politician and major cultural figure, Georges Clémenceau encounters both the First World War and the representatives of an art freed from the codes of the Academy.

19 August 2023

The Ribbank Dresser

An emblematic piece of Dutch furniture, the ribbank was also a powerful symbol of social success in the 17th century.