Since Antiquity, boats and the journeys on board have naturally been a subject often declined, although they are more often focused on symbolism than on the nature and veracity of the marine environment. Emblematic example, the Egyptians considered the boat of Re as an allegory of time and two mythical boats alternated day and night, making the days follow one another. The Mândjyt bark was used for daytime travel while the Mesektet bark was the one on which the god sailed at night. Pushing the metaphor into light and darkness, the boat also served to symbolize the passage from life to death.

In ancient Greece, mythology settled in the fragmented geography of the Mediterranean archipelago, historical and mythical voyages by boat are legion: the return of Odysseus is undoubtedly the most famous and is the allegory of the dangers of the sea through several adventures including that of the mermaids. However, the sea is not a subject in itself; it is the adventures and the exchanges that it allows that interest the artists.

Seascapes: the sea and the ocean as landscapes for boats

The sea and the ocean have never been entirely absent from painting, but they have long stood as a background landscape to human history and much more rarely as a subject in its own right, worthy of interest. The reason is undoubtedly simple: this hostile and unknown environment is worrying and we prefer to represent what allows us to resist it, to stay alive. Humans have indeed lived longer without knowing what was to be found beyond and below the oceans than in a perfectible knowledge of a surface making up the majority of the planet. The construction of myths, each more terrifying than the other (gigantic and monstrous creatures capable of engulfing entire ships, suddenly submerged flourishing cities, etc.) made it possible to overcome ignorance and find explanations for inexplicable phenomena without the science or unknown creatures.

As far as Western art and the Mediterranean basin are concerned, some interest in the marine environment seems to emerge during the Renaissance. If the hagiographic representation is a pretext to paint the sea, the first representations of ports or the sea testify to a thrilling interest in the ocean. At a time when the discovery of the New World and maritime explorations awaken a growing interest in this little-known space, interest is growing for this dangerous environment but harboring unsuspected richnesses.

Vittore Carpaccio (1465 – 1525-26) represents in 1516 the lion of Saint Mark with the arsenal of Venice as background while in these same years, Joachim Patinir (1480/1485-1524) applies his theories to the marine horizon layers of colors for painting landscapes.

But it was further north in Europe that the seascapes, from the 16th century, would truly find their artists and their audience.

Dutch painting, the cradle of seascape paintings

The political, economic and religious context of the Netherlands in the 16th century served as a backdrop for the soon to be flamboyant development of seascape painting. The Protestant Reformation plays a founding role in the history of this country and the culture that accompanies it, particularly in terms of artistic representation.

The restriction of art in religion favors the emergence of a secular art, largely dedicated to a commercial bourgeoisie fond of portraits and paintings honoring what makes its wealth: trade and, above all, maritime trade.

Dutch painters demonstrate a virtuosity that has a lasting mark on painting. Attention is paid as much to the technical veracity of the ships and the situations in which they are represented as to the interpretation of this landscape. This is an opportunity for these artists to demonstrate a fascinating dexterity for atmospheric rendering. Helped by the technical development of oil painting, Dutch painters translate the play of light between sky and sea and attract the attention of prestigious sponsors.

Soon, the Dutch navies became the business of specialists and big names stood out, including Willem van de Velde (1611 – 1693), Ludolf Backhuysen (1630-1708) and Abraham Willaerts (1603-1669). These seascapes bring together several subjects including the essential port scenes or naval battles.

Faced with the Dutch maritime power, England does not have to be ashamed of its fleet. And when in 1678 the war of Holland opposing for 6 years France and its allies (of which England is a part), results in the defeat of the United Provinces and its allies, many Dutch seascape painters emigrate to England . Their services quickly find sponsors happy to be able to celebrate the success of a nation already well deployed throughout the world thanks to its fleet and its colonies. Thus, William van de Velde and his son emigrated to England when the war had just broken out, in 1672.

Seascape Painting in France

In France, the Academy of painting and sculpture created in 1648 at the instigation of Charles Le Brun does not consider seascapes as a subject of great interest, unless they are the scene of a history painting, subject placed at the top of the hierarchy of genres. While the theme seduced a large audience of aristocrats across the Channel, French seascapes still had to wait nearly a century before finding their way. Although this path is largely dictated by royal propaganda.

Because it was on the order of the Marquis de Marigny (1727 – 1781), director of the King’s Buildings, that Joseph Vernet (1714 – 1789) was invited in 1750 to produce a series of large paintings representing French ports. The commission is spectacular since it aims for a set of 24 works. The painter endeavors to represent the teeming activity of the French ports, the vivacity of the economic exchanges with the colonies and the prosperity of a kingdom and the activities specific to each of these ports.

The Seven Years’ War (1756 – 1763) put a stop to this grandiose project: the finances were lacking and the king was therefore content with the 15 canvases already painted by the artist. This first major suite, however, marks the entry of seascapes into a painting considered halfway between history painting and landscape. It also earned Vernet the title of “Painter of the King’s Navy”. The success of these fifteen paintings is such that the painter no longer has to worry about his career. Orders from individuals flock to his workshop and among them, nothing less than those of Catherine II of Russia.

Jean-François Hue (1751 – 1823), a pupil of Vernet, received an order from the Constituent Assembly in 1791 to complete the suite of Ports de France begun by his master. He produced a view of Lorient and three views of Brest.

The Revolution and the Napoleonic period will not have the taste of seascapes other than those related to history painting and in this sense a first official list of painters of the Navy is published under the July Monarchy. The first two artists so named are Louis-Philippe Crépin (1772 – 1851) and Théodore Gudin (1802-1880).

For the latter, the seascapes are a matter of knowledge and experience. Gudin thus asserts that one must have been a sailor to paint the sea. No doubt this point of view is a guarantee of seriousness as the seascapes focus more on the ships than on the sea itself. But at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution and its upheavals – from the invention of the paint tube to the development of seaside stays thanks to the railway – seascapes painting was about to enter a new era. The sea and the ocean become the subjects in their own right of modern painters for whom the human presence in the paintings becomes anecdotal or even useless.

Seascape Painting: the Sea and the Ocean as a Subject Worthy of Interest

Romantic artists were among the first to seize the evocative power of the sea and the ocean. The immensity and the dangerousness, the calm and the storm are the mirror of the tormented soul of the artist. While the industrial machine rhythms the cities and interferes everywhere in daily life, the romantics aspire to a return to nature, to the admiration of an untamed wild nature.

Both romantic and impressionist, William Turner (1775 – 1851) tries his hand at daring paintings, between movement and color, outpourings surprisingly suited to render the confusion reigning in the heart of the unleashed elements.

Realism did not escape this wave and Gustave Courbet (1819 – 1877) devoted himself to it with talent by creating a series of “Seascapes”.

At the same time, the Barbizon school also tried its hand at seascapes in remarkable impressionist flights. All attention is focused on the luminosity of which – one guesses the rapid changes – on a sea that is often calm or painted at low tide. Unlike romantics and realists, softness and serenity invite introspection and reflection. Charles-François Daubigny (1817 – 1878) in particular paints contemplative paintings in virtuoso palettes.

The Impressionists took over seascapes with enthusiasm. The development of leisure and beach scenes allowed Eugène Boudin or Claude Monet – to name but a few – to explore a new way of observing and painting the sea. The versatile nature of the shore, a place of tranquility for some and work for others, is represented as a quiet but formidable force. In these canvases, the sea or the ocean are the setting for a distant rolling, a coming and going deeply inscribed in the character of the inhabitants. It is no longer a question of imposing ships but of a modest daily life made majestic by the immensity of the sea. Normandy or Brittany are then the favorite destinations of artists thanks to the railway which made them accessible.

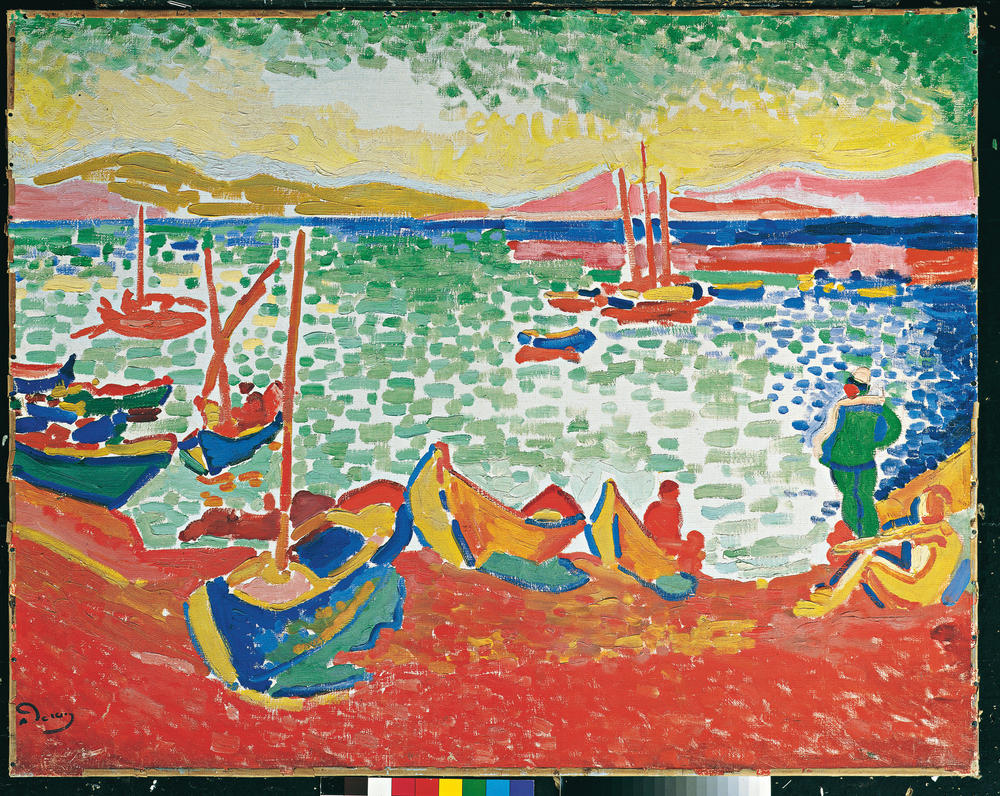

At the turn of the 20th century, the Mediterranean and its azure waves attracted modern painters, the Fauves first, then the Cubists. Under their brushes, it is no longer a dangerous environment that sparkles beyond the pebbles but a joyful, bright and colorful playground where boating seduces new enthusiasts every day.

André Derain (1880 – 1954) fell in love with Collioure and offered an interpretation between pointillism and fauvism, in a shimmering palette.

Paul Signac (1863 – 1935), Albert Marquet (1875 – 1947) or even Charles Lapicque (1898 – 1988) paint seascapes with a very modern sensitivity where we read the changes in society: the characters play and walk on the beach, the boats are less for fishing than for pleasure. These painters in particular know something about it since all of them, like Louis-Mathieu Verdilhan (1875 – 1928), appear in their time on the official list of Navy painters.

The French Navy Painters

Founded in 1830 under the July Monarchy, the body of Navy painters is an institution to which all artists in love with the sea aspire. Although the status of these artists remained unclear for almost a century, it was clarified thanks to a decree signed in 1920. From then on, the title “painter of the Navy Department” was granted by the Minister of Defense for a renewable period of five years to artists who had devoted their talent to the study of the sea, the navy and people of sea. If no compensation accompanies this title, it nevertheless offers some advantages and the honor of being able to add a naval anchor next to the artist’s signature as part of an official order. Within the Navy painters themselves, there are two categories: approved painters appointed for a renewable period of three years and permanent painters.

Finally, let’s add a last category, unofficial, unrecognized, in the shadows and shining by its humility, that of the sailors themselves. For centuries, and more particularly from the 19th century – when painting became an affordable consumer good – sailors were the authors of ex-voto or works keeping the memory of their boat. These are often naive paintings but testifying to the ambiguous link between men and the sea. Those preserved in museums today date back to the 17th century.

Between fascination and terror, the ocean is a source of inspiration as rich as it arouses contradictory feelings. Today this sensitivity is expressed in many artistic mediums, from photography to cinema, mediums now registered on the official list of artists of the Navy.

Marielle Brie

Art Historian for Art Market and Cultural Media

Author of the blog Objets d’Art et d’Histoire

Autres ressources et documentations

17 April 2025

The Middle-Ages Furniture

Rare and highly sought-after, Middle-Ages furniture is making a strong comeback. An overview of this market, where enlisting the guidance of a professional is strongly advisable.

18 March 2025

Murano Glass Furniture

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Murano glassmakers have been exploring new horizons. After classic lighting and decorative art, Murano glass is now used to adorn…

16 December 2024

A bronze triton after the sculptures of François Girardon (1628 – 1715) in Versailles

This fountain element is all the more admirable as it is sculpted after the masterpieces of the Pyramid Basin, on the parterre of the North Wing of the Versailles gardens.

18 November 2024

Tyco Bookcase, by Manfredo Massironi, for Nikol International

A pure creation of optical art research in the 1960s, the Tyco library shelf designed by Manfredo Massironi invites the viewer to bring the work of art to life on a daily basis.

3 August 2024

The Ocean Liner Style

In the 20th century, the immense ocean liners connecting the Old Continent and the New World were ambassadors of tastes and innovations on both sides of the Atlantic.

15 July 2024

An 18th Century Shell Box

From the Regency to the death of Louis XV, the art of the shell was the center of all attention.