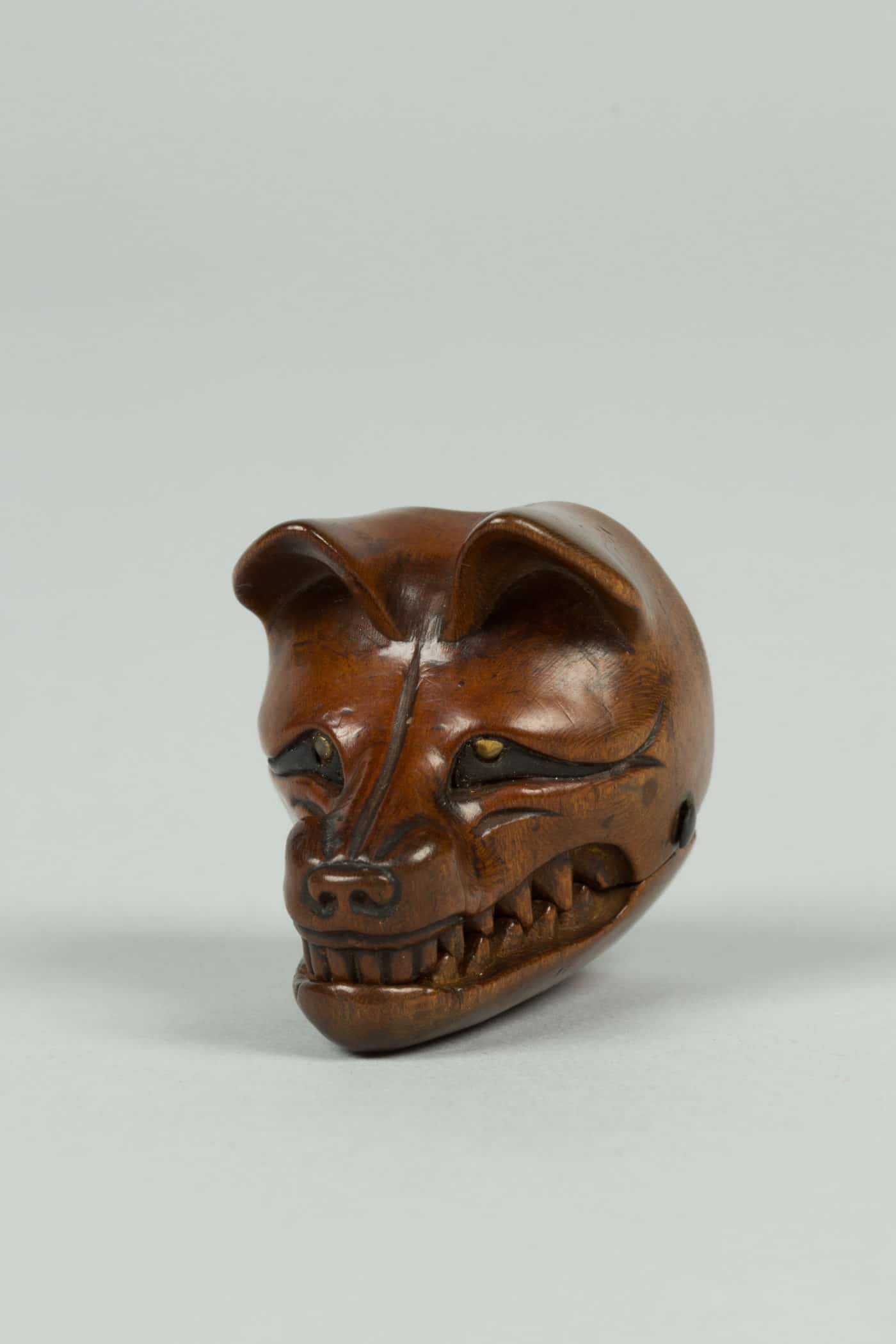

Pronounced net-ské (the u – as in Hokusai – is silent here), these small, surprising, delicate and often funny sculptures are the object of special attention among Japanese art lovers. The scholar knows the slightest symbolisms, the different materials and sometimes even the most confidential regional schools. The wealth of netsuke is a world unto itself and their study can occupy a lifetime; let us start here with an introduction that will simplify yours.

The Origin of Netsuke

The etymology of the word gives a glimpse of its modest and discreet origins because netsuke is originally nothing more than a tie made of a root: “ne” root, “tsuke” tie. The development of this little object did not augur a future as bright as the one we know. The netsuke is first used in China where it is, in the 16th century, a piece of bamboo or root, sometimes a shell. Then it reached Japan in the 17th century. These small objects that are quickly carved are indispensable accessories to the obi belt of the kimono. Of course, it was customary – especially for women – to carry small everyday objects in the sleeves of one’s kimono. But the sleeves are no longer enough – or the aesthetics are not good enough – so it is finally decided to hang small cases on the belt.

Seal or medicine boxes(inrô), writing and smoking utensils (yatate), and even pipe cases(kiseruzutsu) were generally referred to as sagemono, literally hanging objects. These had to be held by a cord, itself cleverly tied to the belt and the unsightly knot hidden behind the netsuke.

This is an essential characteristic that allows anyone to determine whether or not they are facing a netsuke. Do you notice two holes (himotōshi) for passing the sagemono cord? Are they wide enough to slip a lanyard through? Do they allow to position correctly the netsuke at the belt? Is the patina more pronounced on the obverse than on the reverse? All these questions allow to recognize a netsuke that has been used. If, however, the himotōshi seems no more functional than the patina is uniform then perhaps it is a netsuke intended to satisfy the Western infatuation with this Nipponese art form. And that doesn’t take away (almost) anything from its value!

The Western Craze for Netsuke in the 19th Century

When, in 1854, the Japanese harbours finally opened their doors to foreign trade, Westerners were amazed to discover a mysterious culture, far removed from anything they knew at the time. The reverse is no less true! And the introduction of Western suits into Japanese society was probably one of the most rapid and visible changes. While the kimono retreats into the confines of the private sphere, the demand for netsuke does not suffer from this sudden lack of interest because, at the same time, demand continues to grow to satisfy Western travellers such as the Goncourt brothers, Pierre Loti and Emile Guimet. The latter marvel at these small refined objects, perfect souvenirs of this fascinating Japan. Once back in Europe, travellers arouse the curiosity of their compatriots even more. The craze for Japanese art was first expressed at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, a famous exhibition during which visitors discovered Japanese furniture, prints and art objects. It was so successful that the Japanese section was repeated at the 1878 Exposition Universelle, where the famous prints by the engraver Hokusai (1760 – 1849) were exhibited.

Paris swears by Japan: in the most popular salons, one furnishes lacquered creations or those signed Gabriel Viardot, on which bronzes and sculptures are displayed. At the unique Clémence d’Ennery (1823 – 1898), there are more than 300 netsuke that can be admired, all bought at the Bon Marché or in antique shops. On the other side of the globe, in the Japanese archipelago, specialized craftsmen, the netsuke-shi, fine-tune a production whose variety naturally lends itself to collection.

Shapes and Materials: the Diversity of Netsuke

We can easily distinguish a few categories of netsuke forms. In each of these categories, there will be almost as much diversity of styles as there will be netsuke-shi – of which there are now nearly 1200 names, throughout the 18th, 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. Of course, there are some great names that are highly sought after, but the anonymous creations or those of small masters are no less interesting.

The katabori are the best known. They are carved in the round and realistically represent animals or characters, sometimes even simple objects because the Shinto influence maintains that no living being, element or object is without a soul. Everything is worthwhile.

The kagamibuta are round and enclose a plate of a different material to the crown, often ivory.

Manju is named after a famous cake of the same name. They are like the round and flattened kagamibuta but in one piece and are only engraved, painted or carved in low relief.

The ryūsa are round or oval but carved in high relief or openwork. In the case of these netsuke, the himotōshi is unnecessary since the lanyard can be passed through the hollowed out patterns, usually birds or flowers.

The sashi are very elongated and are inserted directly into the obi. Usually the himotōshi is pierced at one end.

The ichiraku are made of weaving or braiding of flexible materials such as bamboo or rattan but sometimes also of metal or metal wires.

Contrary to common belief, ivory is not the main material used for netsuke. Craftsmen widely used wood in all kinds of species (ebony, boxwood, yew, etc.) as well as coral, porcelain, pure lacquer, horn, bone, dried fruits and gourds and later metal. It would also be wrong to believe, as in Europe, that the material dictates the value! It is the qualities of the carving and the chiseling that will distinguish a beautiful netsuke from a more ordinary one. Unless one recognizes in these small sculptures a rarely sculpted subject…

The Free Expression of Netsuke-Shi

Since it was an object of little interest to the powers that be – preferring, under the Edo shogunate (1603 – 1868), to show ostentation on swords in particular – the craftsmen enjoyed a certain freedom of expression and, bravely, sometimes tried their hand at satire, parody or parable. Otherwise, each craftsman drew according to his taste from a rich iconography marked by multiple influences. This makes today’s task as difficult as it can be childish for those who try to identify the obvious or hidden references of a Japanese netsuke.

All genres are represented: portraiture, still life, genre scene, landscape, animal, religious, Kabuki and Nō theatre, caricature or eroticism. Let us add the fantastic and mythical bestiary because the Japanese craftsman has at his disposal the influences of the great myths and characters of Shintoism, Buddhism and Taoism, as well as those of superstitions. In Japanese culture, the fantastic and the trivial are not independent of each other, quite the contrary. The permeability of the supernatural and the everyday opens the doors to a captivating animism.

From China, Japan inherited some auspicious motifs such as the bat symbol of happiness or the peach symbol of longevity.

When it comes to characters, netsuke like to portray all kinds of subjects, from the humblest trade to professions of the highest rank. The characters are generally treated in a naturalistic style, always in search of a certain bonhomie that can be found in the treatment of the deities. Among these, there are of course monsters or spirits but especially some very popular characters.

Hoteï for example is among the most represented. An important figure in Buddhism, he is depicted with his monk’s habit nonchalantly open on his bountiful belly, always joyful and for good reason! He is the god of abundance. It is the Japanese equivalent of the famous Chinese Budai.

Don’t worry about Fukurokuju’s impressive cranial deformation! This character of legendary wisdom and canonical age is the Shinto god of happiness, wealth and longevity. This is literally what its name indicates: fuku “happiness”, roku “wealth” and ju “longevity”. He leans on a cane, holds a fan and a crane sometimes accompanies him. In China, this character is embodied in three distinct figures, the gods Fú, Lù and Shòu united under the generic name of San Xing (the three stars).

Finally, animals are among the most appreciated figures and are declined in different forms of netsuke. Often, however, it is not just a question of representing the ordinary beauty of an animal and the attentive observer often recognizes animals from the Chinese zodiac, each associated with a virtue or a quality.

In the 18th century, the art of netsuke was still confined to the workshops of Buddhist sculptors or mask makers. But little by little, the demand requires specialization. From the middle of the 18th century, the making of netsuke was no longer a secondary activity and some signatures began to appear at the same time as schools were created. However, it is advisable to remain cautious as for the signatures of netsuke, only the opinion of a specialized expert will be able to inform you. Indeed, some apocryphal signatures pay tribute to a master without the work being by his hand!

If netsuke dated with certainty to the 18th century are rare and sought after, those from the first half of the 19th century are just as remarkable. This singular art is then at its peak and shows a delicate sophistication characteristic of Japanese art. The second half of the 19th century, boosted by European demand, produced pieces of all qualities with, always, a variety of subjects that made the richness of netsuke collections and the admiration of the most passionate Europeans.

Marielle Brie

Art Historian for Art Market and Cultural Media

Author of the blog Objets d’Art et d’Histoire

Autres ressources et documentations

29 March 2024

A Micro-mosaic Grand Tour Cross

An emblematic art of the Grand Tour, micro-mosaics rival painting in its most refined productions.

19 March 2024

The Cordoba Leather or Gilded Leather

This famous leather gave its letters of nobility to Spanish production drawing generously on oriental know-how known since Antiquity.

6 February 2024

A Solid Silver Inkwell, 1860 – 1890

This solid silver inkwell is a true sculpture in itself.

4 December 2023

Chinese Opium Den Pillow, 19th Century

A surprising object to our Western eyes, Chinese rigid pillows have long been preferred to their fabric counterparts.

22 November 2023

Georges Clémenceau (1841 – 1929) Bust

A major politician and major cultural figure, Georges Clémenceau encounters both the First World War and the representatives of an art freed from the codes of the Academy.

19 August 2023

The Ribbank Dresser

An emblematic piece of Dutch furniture, the ribbank was also a powerful symbol of social success in the 17th century.